Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein. This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER. Nutrition is what you eat and drink and how your body uses it. Good nutrition is important for good health. A healthy diet includes a variety of foods and liquids that have nutrients (vitamins, minerals, proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and water) your body needs. Good nutrition for people with cancer may differ from what we think of as healthy People with cancer often need to follow diets that are different from what we think of as healthy. For most people, a healthy diet includes lots of whole grains, fruits and vegetables, modest amounts of protein, and small amounts of sugar, alcohol, salt, and unhealthy fats. When you have cancer, though, you may need extra protein and calories. To eat enough protein and calories, your diet may need to include more meat, fish, eggs, dairy, fats, and plant-based proteins than someone without cancer. The extra protein and calories will help you keep your strength up to deal with the side effects of treatment, prevent malnutrition, and maintain your best possible quality of life. A registered dietitian can help make sure you get the right amount of protein and calories during and after cancer treatment. They will work with you, your family, and the rest of your medical team to help manage your diet. Find a registered dietitian in your area. Plan nutrition before cancer treatment During treatment, you may be tired and not feel well. Being tired can make it harder to grocery shop, cook, and eat. Planning meals before treatment will make it easier to eat during treatment. To plan meals and snacks before treatment, try these tips. Shopping tips: Meal prep tips: Tips for accepting help from others: Effects of cancer treatment on nutrition Both cancer and cancer treatments may cause side effects that affect your taste, smell, appetite, and ability to eat enough food or absorb the nutrients from food. This can lead to malnutrition. People with certain cancers are more likely to have problems eating. These cancers include those that affect your digestive system directly, such as cancers of the head and neck, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, or colon. But people with any type of cancer can find it hard to eat well because of the effects of cancer treatment. When malnutrition is not managed in people having cancer treatment, it can lead to cancer cachexia. Cancer cachexia is a wasting syndrome that can cause weakness, weight loss, and fat and muscle loss. It can occur even when you are eating well. Learn more about Weight Changes, Malnutrition, and Cancer and Cancer Cachexia. Chemotherapy and eating problems Chemotherapy uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. But these drugs may also kill healthy cells that grow and divide quickly, such as cells in the mouth and digestive tract. This can cause eating problems and other side effects, including: If you are on chemotherapy, you may have a high risk of infection, including from food (foodborne illness). That is because chemotherapy can reduce the number of your white blood cells, which fight infection. It is important that you and your caregivers learn about how to safely prepare food and how to avoid foods that may cause infection. Learn more about Chemotherapy to Treat Cancer. Hormone therapy and eating problems Hormone therapy may be used to slow or stop cancers that rely on hormones to grow, like breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer. Hormone therapy adds, blocks, or removes these hormones. These drugs can cause weight gain and other side effects, including: Learn more about Hormone Therapy to Treat Cancer. Immunotherapy and eating problems Immunotherapy uses your immune system to fight cancer. The side effects of immunotherapy are different for each person and depend on the type of immunotherapy drug. Immunotherapy may cause fatigue, which can lead to a poor appetite. Learn more about Cancer Fatigue. Common nutrition-related side effects caused by immunotherapy include: Learn more about Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer. Radiation therapy and eating problems Radiation therapy kills cancer cells and healthy cells in the area that is being treated. Radiation therapy to any part of your digestive system has side effects that cause eating problems. Most of the side effects begin 2 to 3 weeks after radiation therapy begins and go away a few weeks after it is finished. But some side effects can last for months or years after treatment ends. Learn more about Late Effects of Cancer Treatment. Fatigue, which can lead to a poor appetite, is a common side effect of radiation therapy. Learn more about Cancer Fatigue. Radiation therapy to the brain or head and neck may cause: Radiation therapy to the chest may cause: Radiation therapy to the abdomen, pelvis, or rectum may cause: Learn more about Radiation Therapy to Treat Cancer. Stem cell transplant and eating problems People who have a stem cell transplant have special nutrition needs. Medications used before or during a stem cell transplant may cause side effects that keep you from eating and digesting food as usual. Common nutrition-related side effects caused by stem cell transplant include: If you have a stem cell transplant, you have a high risk of infection, including from food (foodborne illness). That is because treatment given before your transplant reduces the number of your white blood cells, which fight infection. It is important that you and your caregivers learn about how to safely prepare food and how to avoid foods that may cause infection. After a stem cell transplant, you are also at risk of acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). GVHD may affect your digestive tract, skin, or liver and change your ability to eat or absorb nutrients from food. Learn more about Stem Cell Transplants in Cancer Treatment. Surgery and eating problems Surgery is a common part of cancer treatment. Surgery that removes all or part of certain organs can affect your ability to eat and digest food. After any surgery, your body needs extra energy and nutrients to heal wounds, fight infection, and recover. If you are malnourished before surgery, you may have trouble healing. Common nutrition-related side effects caused by surgery include: Learn more about Surgery to Treat Cancer. Targeted therapy and eating problems Targeted therapy is a type of cancer treatment that targets proteins that control how cancer cells grow, divide, and spread. It may disturb normal function of your digestive system and cause: Other problems might include taste changes and a dry or sore mouth. Learn more about Targeted Therapy to Treat Cancer. Food safety during cancer treatment Some cancer treatments can weaken your immune system. This makes it harder for you to fight infections, including foodborne illnesses. So, you need to take special care in the way you handle and prepare food during your cancer treatment. Keep foods at safe temperatures, scrub raw vegetables and fruits, and be careful to use separate utensils, plates, and cutting boards when preparing meats and produce. Learn more about food safety for people with weakened immune systems. Learn more about risk of Infection During Cancer Treatment. Nutrition screening and assessment during cancer treatment If you have trouble eating and maintaining your weight, your nurse, doctor, or registered dietitian may ask you a series of questions to find out if you are malnourished or are likely to become so. To assess your nutrition status, you may be asked about: If you are at risk of poor nutrition or malnutrition, your doctor will refer you to a registered dietitian. A registered dietitian can do an assessment, which reviews your: Based on this information, the registered dietitian will create a nutrition care plan. This plan includes ways you and your family can improve your eating and address any nutrition problems that you are having. Ways to manage nutrition problems caused by cancer treatments When side effects of cancer or cancer treatment affect normal eating, there are ways to help you get the nutrients you need. Ways to manage appetite loss, weight loss, and early satiety If you have loss of appetite, weight loss, or feel full too quickly, these tips may help: If you continue to struggle to eat and keep up your weight, you and your treatment team can discuss other nutrition support options. These options may include tube feeding or IV nutrition. You may also take medicines that increase appetite. Learn more about Weight Changes, Malnutrition, and Cancer. Ways to manage nausea and vomiting Nausea is when you feel sick to your stomach, as if you have the urge to throw up. Vomiting is when you throw up. Nausea and vomiting are common side effects of cancer treatments, including chemotherapy and radiation therapy. But there are medicines that often prevent or relieve nausea and vomiting before they start or become a problem. When you vomit, you may become dehydrated and lose a lot of electrolytes. Electrolytes are minerals, such as potassium, sodium, and calcium that help balance body fluids and support your heart, nerve, and muscle functions. Talk to your dietitian about which drinks can help prevent dehydration and how much you should drink. Learn more about Nausea and Vomiting and Cancer Treatment. Ways to manage dry mouth Dry mouth occurs when you have less saliva than you used to. Having less saliva can make it harder to talk, chew, and swallow food. Dry mouth can also change the way food tastes. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the head or neck can damage the glands that make saliva. Immunotherapy and some medicines can also cause dry mouth. If you have dry mouth: Talk with your doctor or dentist about using artificial saliva or a similar product to coat, protect, and moisten your mouth and throat. Learn about mouth and throat problems caused by cancer treatments. Ways to manage mouth sores Cancer treatments can harm fast-growing cells in your mouth. Radiation therapy to the head or neck, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy can cause mouth sores (little cuts or ulcers in your mouth) and tender gums. Dental problems or mouth infections, such as thrush, can also make your mouth sore. Visit a dentist at least 2 weeks before starting immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy to the head and neck. Your mouth and gums will most likely feel better once cancer treatment ends. If you have mouth sores: Ways to manage sore throat and trouble swallowing Chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the head and neck can make the lining of your throat inflamed and sore, a problem called esophagitis. It may feel as if you have a lump in your throat or that your chest or throat is burning. You may also have trouble swallowing. These problems may make it hard to eat and cause weight loss. Some types of chemotherapy and radiation to the head and neck can harm fast-growing cells, such as those in the lining of your throat. Your risk of sore throat, trouble swallowing, or other throat problems depends on: If you have a sore throat or trouble swallowing: Talk to your doctor about tube feedings if you cannot eat enough to stay strong. Ways to manage taste and smell changes Cancer treatment, dental problems, or the cancer itself can cause changes in your sense of taste or smell. Food may have less taste or certain foods (like meat) may be bitter or taste like metal. Sometimes, foods that used to smell good to you no longer do. Although there is no way to prevent these problems, there are things you can do to manage them. And often they get better after treatment ends. Ways to manage a salty taste: Ways to manage an overly sweet taste: Ways to manage a loss of taste or "off" taste: Ways to manage bitter and metallic tastes: Ways to manage smell changes: Types of nutrition support if you cannot eat Sometimes, despite your best efforts, you may not be able to eat enough to stay strong. If this happens, nutrition support through a feeding tube may be a good option. Nutrition support helps if you cannot eat or digest enough food to stay nourished. Staying nourished helps increase the chance of receiving treatment without unplanned breaks. Your doctor or dietitian will discuss nutrition support with you if they think it will help. There are two types of nutrition support, enteral and parenteral nutrition. Enteral nutrition Enteral nutrition gives you nutrients in liquid form through a tube that is placed into the stomach or small intestine. There are two types of feeding tubes: The type of formula used is based on your specific nutritional needs. There are formulas for people with special health conditions, such as diabetes, or with other needs, such as observing religious or cultural norms. Some people can still eat by mouth when using enteral nutrition. Before doing so, it is important to ask your doctor if it is safe for you. Parenteral nutrition Parenteral nutrition is used when you cannot take food by mouth or use a feeding tube. Parenteral feeding does not use the stomach or intestines to digest food. Nutrients are given to you directly into the blood through a catheter inserted into a vein. These nutrients include proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals. As with enteral feeding, some people can eat by mouth when using parenteral nutrition. Ask your doctor if it is safe to eat by mouth while receiving parenteral nutrition. The catheter may be placed into a vein in the chest or in the arm. A central venous catheter is placed beneath your skin and into a large vein in the upper chest. The catheter is put in place by a surgeon. This type of catheter is used for long-term parenteral feeding. A peripheral venous catheter is placed into your vein in the arm. A peripheral venous catheter is put in place by trained medical staff. This type of catheter is usually used for short-term parenteral feeding or if you do not have a central venous catheter. You will be checked often for infection or bleeding at the place where the catheter enters the body. Nutrition therapy for the end of life If you are nearing the end of life, the goal is to provide the best possible quality of life and control symptoms that cause discomfort. Your nutrition goals will be specific to you. Common symptoms that can occur at the end of life include: The focus is on relieving these symptoms, rather than getting enough nutrients. You and your family can decide how much nutrition and fluids you will be given at the end of life People at the end of life often do not feel much hunger at all and may want very little food. Sips of water, ice chips, and mouth care can help with thirst. Food and fluids should not be forced on someone who is at the end of life. Doing so can cause discomfort or choking. You and your loved ones have the right to make informed decisions. Your religious and cultural preferences may affect your decisions. The health care team and a registered dietitian can explain nutrition needs and the benefits and risks of using tube feeding or IV nutrition at the end of life. Possible benefits of nutrition support for people expected to live longer than a month include: The risks of nutrition support at the end of life include: Learn more about nutrition support and what to expect during the last days of life. Appetite loss and weight loss are common side effects of cancer and cancer treatments. Anyone with cancer might lose their appetite and lose weight. But you are more likely to lose weight if you have head and neck, lung, pancreatic, or liver cancer or cancer in the upper digestive system. Upper digestive system cancers include cancers in the throat, esophagus, stomach, and the first part of the small intestine. Appetite loss often leads to eating less than your body needs, which leads to weight loss. Weight loss can also occur when you burn more calories than you are taking in. Weight loss can lead to malnutrition. Although cachexia also causes weight loss, cachexia and weight loss are different and treated differently. Learn more at Cancer Cachexia. Side effects of cancer treatment that cause problems with eating include: Other factors that may cause appetite loss and weight loss during cancer treatment include anxiety, pain, depression, and fatigue. Learn more about Emotions and Cancer. Ways to manage appetite loss and weight loss in people with cancer If you start to lose your appetite, talk with your doctor or registered dietitian. Speak with them right away if you start to lose weight. Your dietitian can help you and your family manage your weight loss. Here are some tips that may help. Tips about foods to eat: Tips on when to eat: Tips about when and what to drink: Meal prep tips: Other tips to help improve eating: Medicine to manage appetite loss from cancer and cancer treatment If you are not able to keep your appetite up, talk with your doctor about appetite stimulants. These are medicines that increase appetite and can cause weight gain. Increased appetite, weight gain, and cancer Although many people with cancer have appetite loss and lose weight, you may gain weight during cancer treatment. Weight gain is more common if you have ovarian, breast, or prostate cancer. Each person is different, so even if you have one of these cancers, it does not mean you will gain weight. And you may gain weight if you have a different type of cancer. If you gain weight during your cancer treatment, let your doctor know so they can assess the cause and type of weight gain. Small weight fluctuations during cancer treatment are normal and expected. But if weight gain is sudden, such as 5 pounds in a week, or does not stop, tell your doctor right away. Causes of weight gain in people with cancer Fluid retention. Some cancers may cause weight gain due to the size of the tumor or the buildup of fluid. There are different types of fluid buildup, but they all can cause you to gain weight. Learn more at Edema (Swelling) and Cancer Treatment. Increased appetite. Increased appetite and food cravings that result in weight gain may occur from the cancer itself, cancer treatment, or medicines used with cancer treatment. Metabolic changes. Hormone therapy may cause weight gain by lowering sex hormones. When you have lower levels of sex hormones, your metabolism slows. Our metabolism is the rate at which we burn energy. A slower metabolism means you burn less energy, which makes it easier to gain weight. Some hormone therapies and chemotherapy may lead to early menopause in women. Early menopause may decrease your metabolism and cause weight gain. Medications. Steroids, which are often given during cancer treatment, increase appetite and make you want to eat more. When we eat more calories than our body burns, we gain weight. If you take steroids, try to eat foods high in fiber and protein at each meal to help you stay full. Steroids may also cause weight gain by causing your body to hold onto water (fluid retention). If you retain water, you may look and feel swollen. Learn more about fluid retention at Edema (Swelling) and Cancer Treatment. Decreased activity. Many cancer treatments can cause fatigue and pain, making it hard to be active. Being less active may in turn lead to weight gain. Talk to your doctor about how to manage problems like fatigue or pain to stay as active as possible. Learn more at Cancer Fatigue and Pain and Cancer. Ways to manage increased appetite and weight gain in people with cancer Here are some tips to manage increased appetite and slow or stop weight gain. Talk with your doctor or dietitian about these tips and which ones are right for you. Tips about foods to eat: Tips about foods to limit: Grocery shopping tips: Meal prep tips: Other ways to help with weight gain: If you have swelling from steroids, try limiting or avoiding foods that are high in sodium, such as: If you don't want to cut out these foods, look for lower sodium options. You can look at the front of a product to see if it says, "low sodium," "very low sodium," or "sodium free." Instead of using the saltshaker, use dried or fresh spices like garlic and onion powder or fresh basil and oregano. Talk with your doctor and dietitian before going on a diet to lose weight. If you eat because of stress, fear, or depression, think about talking with a counselor. Your doctor might also prescribe medicine to help with these feelings. Learn more about Emotions and Cancer. Malnutrition and cancer Malnutrition is when your body doesn't get enough energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Causes of malnutrition in cancer Malnutrition can be caused by the cancer itself, the side effects of cancer treatment, or both. Cancer and its treatment can cause malnutrition in many ways. They can decrease your appetite, make you feel full quickly, and change your sense of taste and smell. These changes may cause you to eat less. In fact, decreased appetite or appetite loss is a main cause of malnutrition in people with cancer. Cancer may also lead to malnutrition by causing problems with swallowing, digestion, and absorption of your food. Common treatment side effects that increase the risk of malnutrition are: Cancer and cancer treatments may also cause fatigue, pain, anxiety, distress, and depression, all of which can make eating a challenge, both physically and emotionally. Talk to your doctor and registered dietitian about any of your side effects and concerns. Your team is there to support you and help you manage these challenges. Problems caused by malnutrition Malnutrition can cause you to be weak, tired, and not able to fight infection or even finish cancer treatment. Studies show that malnutrition can decrease your quality of life and become life-threatening. Screening for malnutrition Your health care team may use nutrition screenings and assessments to catch eating problems early and measure your risk of malnutrition. Ask your doctor about a nutrition screening before treatment starts and when you should be screened again during treatment. Ways to prevent malnutrition Here are tips to prevent malnutrition. Tips on what to eat: Tips on when to eat: Tips on talking with your doctor or dietitian: If you continue to have trouble eating and are losing weight, your doctor or dietitian might suggest tube feeding (enteral nutrition) or IV nutrition (parenteral nutrition). Learn more about tube feeding and IV nutrition at Nutrition During Cancer Treatment. Getting support for weight changes and malnutrition Support from family and friends. Ask your family and friends to help with meal planning, grocery shopping, cooking, and cleaning. Provide them with a list of your favorite foods and meals they can prepare for you. Support from your health care providers. If you're having trouble with eating and drinking, your doctor and dietitian can help. Your doctor can help you find medicines to manage certain problems and refer you to a registered dietitian. Your registered dietitian is your nutrition expert. They can help you with eating and drinking habits before, during, and after treatment. Support for caregivers. Do not be surprised or upset if your loved one's food preferences change from day to day. There may be days when they do not want a favorite food or say it now tastes bad. Offer gentle support rather than pushing your loved one to eat. Talk with your loved one about ways to manage eating problems. Ask the doctor for a referral to a dietitian and meet with them together. Talk through problems and seek other advice that can help you both feel more in control. Learn more about getting support when your loved one is being treated for cancer at Support for Caregivers of Cancer Patients. Related resources Cancer cachexia is a wasting syndrome that leads to weakness, fatigue, and loss of skeletal muscle (also called sarcopenia) and fat. Unlike malnutrition, it cannot be reversed with nutrition support alone. Cancer cachexia must be treated with medicines and is hard to reverse once it starts. Cancer cachexia is most common in people with advanced cancer. There are three stages of cancer cachexia: What causes cancer cachexia? Scientists don't fully understand how cachexia occurs in people with cancer. But they think that inflammation is the main cause. Increased metabolism, insulin resistance, and hormone changes may also play roles. Inflammation Inflammation can cause appetite loss, loss of muscle and fat, changes in how the body uses nutrients, decreased eating, and increased metabolism. Lab tests show that certain cancers, such as breast, ovarian, and esophageal cancer, can cause inflammation in the body. Changes in metabolism Some cancers can change your metabolism, or how your body uses carbohydrates, protein, and fat from food. Changes may include rapid breakdown of protein and fat stores in the body, causing muscle and fat loss. An increased metabolism also means your body uses more energy. This makes it harder for your body to meet its energy and protein needs, leading to weight loss and possible cachexia. Not all people with cancer have an increased metabolism. But it is common in those with head and neck, lung, and pancreatic cancers and cancers of the upper digestive tract. Insulin resistance People with cancer may have insulin resistance. Normally, after you eat food, insulin tells your cells to allow glucose (sugar) to move from your blood into your cells. But with insulin resistance, the cells no longer respond to insulin. When your cells can't respond to insulin, glucose can't enter your cells and it builds up in your blood, causing high blood sugar (a condition called hyperglycemia). And when glucose cannot get into your cells, it is not available to be used by the cells for energy. This can lead to weight loss and possible cachexia. Changes in hormones Cancer cachexia may also be caused by a change in hormones, chemical messengers that tell your cells what to do. Two groups of hormones are linked with cancer cachexia: catabolic and anabolic hormones. Catabolic hormones break down tissue, and anabolic hormones build tissue. In cancer cachexia, your body has more working catabolic hormones than anabolic hormones. This imbalance leads to muscle breakdown, making cancer cachexia worse. Symptoms of cancer cachexia The most common symptoms of cachexia are: These symptoms can have many causes and may not be a sign of cachexia. It's important to talk with your doctor if you notice these changes. Your doctor can help you manage them and decide if other tests are needed. Ways to prevent cancer cachexia Spotting and treating malnutrition early is the best way to prevent cancer cachexia. Talk to your doctor about regular nutrition screenings during treatment to see if you are at risk of malnutrition and cancer cachexia. Learn more at Weight Changes, Malnutrition, and Cancer. Ways to manage cancer cachexia You need the help of many types of health care providers to manage cachexia. Your doctor may prescribe medicines such as appetite stimulants and anti-inflammatory drugs. They might refer you to a registered dietitian who can suggest nutrition supplement drinks, such as Ensure or Boost. Dietitians can provide nutrition counseling and education for you and your caregivers. If you need it, dietitians oversee nutrition support such as tube feeding (enteral nutrition) and IV nutrition (parenteral nutrition). Learn more about tube feeding and IV nutrition at Nutrition During Cancer Treatment. Your doctor might refer you to physical therapy. Physical therapy can help improve strength and endurance. Getting stronger can help you move better and take part in daily activities, which can help improve your quality of life. If swallowing becomes an issue, your doctor can refer you to a speech therapist. If mouth sores or other mouth problems are getting in the way of eating and drinking, your doctor may suggest you see a dentist. Learn more about managing mouth problems during cancer treatment at Mouth and Throat Problems During Cancer Treatment. Getting support for cancer cachexia Support from family and friends. Cachexia can make you feel tired and unable to do your daily activities. Reach out to your family and friends to help with meal planning, grocery shopping, cooking, and cleaning. Your family and friends will want to know how to help you. If people offer help, accept it. Support from your health care providers. Be sure that your doctor knows about problems you are having. Your doctor can prescribe medicine and refer you to other health care providers as needed. Support for caregivers. It is normal to feel distress when a loved one has cachexia. You might be upset about their weight loss, loss of physical function, and changing appearance. There may be days when your loved one does not want to eat or drink. Offer gentle support rather than pushing your loved one to eat. Ask the doctor for referrals to a dietitian and physical therapist to help your loved one with cachexia. Meet with them together so you know how best to help your loved one. Learning about cachexia can help you know what to expect, which can ease your distress. Learn more about getting support at Support for Caregivers of Cancer Patients. Cancer cachexia often happens at the end of life. To prepare, it might help to talk with the doctor or nurse about what to expect during this time. Learn more at Advanced Cancer. Related resources Last Revised: 2024-12-11 If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions. This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Learn how we develop our content. Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.Nutrition in Cancer Care: Supportive care - Patient Information [NCI]

What is nutrition?

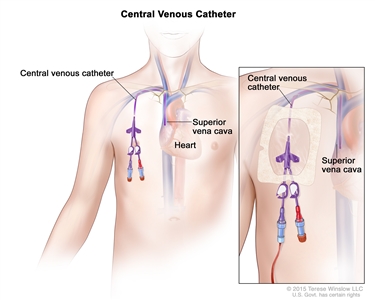

A central venous catheter is a thin, flexible tube that is inserted into a vein, usually below the right collarbone, and guided into a large vein above the right side of the heart called the superior vena cava.

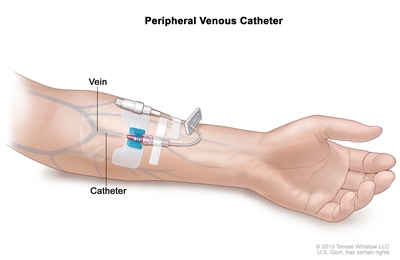

A peripheral venous catheter is a thin, flexible tube that is inserted into a vein. It is usually inserted into the lower part of the arm or the back of the hand.Appetite loss, weight loss, and cancer

What is cancer cachexia?

Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.Nutrition in Cancer Care: Supportive care - Patient Information [NCI]