Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein. This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER. Esthesioneuroblastoma (also called olfactory neuroblastoma) is a very rare small round cell tumor arising from the nasal neuroepithelium. Less than 10% of cases occur in children and adolescents.[1,2] The estimated incidence of esthesioneuroblastoma is 0.1 cases per 100,000 people per year in children younger than 15 years.[3] In the pediatric population, the median age is 10 years, and there are no gender or racial predilections.[2] Despite its rarity, esthesioneuroblastoma is the most common cancer of the nasal cavity in pediatric patients, accounting for 28% of cases in a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program study.[1] References: Figure 1 depicts the areas of the body where esthesioneuroblastoma tumors may form, including the olfactory nerve endings, olfactory bulb, nasal cavity, nasal sinuses, and brain. Most children present with symptoms that may include the following:[1] References: Esthesioneuroblastoma can be histologically confused with other small round cell tumors of the nasal cavity, including sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, melanoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Esthesioneuroblastoma typically shows diffuse staining with neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, and chromogranins, with variable cytokeratin expression.[1] Nine medical centers obtained 66 samples of olfactory neuroblastoma and tumor samples from other cancers, including alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma and sinonasal adenocarcinoma. The tumor samples were analyzed by genome-wide DNA methylation profiling, copy number analysis, immunohistochemistry, and next-generation panel sequencing. Unsupervised hierarchal clustering analysis of DNA methylation data identified the following four distinct clusters:[2] Using this information, the authors developed an algorithm that incorporates methylation analysis to improve the diagnostic accuracy of this entity.[2] References: Review of multiple case series of mainly adult patients indicates that the following may correlate with adverse prognosis:[1,2,3] References: Tumors are staged according to the Kadish system (see Table 1). Correlated with Kadish stage, survival rates range from 90% (stage A) to less than 40% (stage D). Most patients present with locally advanced–stage disease (Kadish stages B and C). Reports of metastatic disease (Kadish stage D) vary among studies and is described at rates of 20% to 30%.[1,2,3,4,5,6] Reports suggest that positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) may aid in staging the disease.[7] References: Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, although the overall incidence has slowly increased since 1975.[1] Children and adolescents with cancer should be referred to medical centers that have a multidisciplinary team of cancer specialists with experience treating the cancers that occur during childhood and adolescence. This multidisciplinary team approach incorporates the skills of the following pediatric specialists and others to ensure that children receive treatment, supportive care, and rehabilitation to achieve optimal survival and quality of life: For specific information about supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer, see the summaries on Supportive and Palliative Care. The American Academy of Pediatrics has outlined guidelines for pediatric cancer centers and their role in the treatment of children and adolescents with cancer.[2] At these centers, clinical trials are available for most types of cancer that occur in children and adolescents, and the opportunity to participate is offered to most patients and their families. Clinical trials for children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer are generally designed to compare potentially better therapy with current standard therapy. Other types of clinical trials test novel therapies when there is no standard therapy for a cancer diagnosis. Most of the progress in identifying curative therapies for childhood cancers has been achieved through clinical trials. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website. Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer. Between 1975 and 2020, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[3,4,5] Childhood and adolescent cancer survivors require close monitoring because side effects of cancer therapy may persist or develop months or years after treatment. For information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors, see Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer. Childhood cancer is a rare disease, with about 15,000 cases diagnosed annually in the United States in individuals younger than 20 years.[6] The U.S. Rare Diseases Act of 2002 defines a rare disease as one that affects populations smaller than 200,000 people in the United States. Therefore, all pediatric cancers are considered rare. The designation of a rare tumor is not uniform among pediatric and adult groups. In adults, rare cancers are defined as those with an annual incidence of fewer than six cases per 100,000 people. They account for up to 24% of all cancers diagnosed in the European Union and about 20% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States.[7,8] In children and adolescents, the designation of a rare tumor is not uniform among international groups, as follows: Most cancers in subgroup XI are either melanomas or thyroid cancers, with other cancer types accounting for only 2% of the cancers diagnosed in children aged 0 to 14 years and 9.3% of the cancers diagnosed in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years. These rare cancers are extremely challenging to study because of the relatively few patients with any individual diagnosis, the predominance of rare cancers in the adolescent population, and the small number of clinical trials for adolescents with rare cancers. References: The use of multimodal therapy optimizes the chances for survival, with more than 70% of children expected to survive 5 or more years after initial diagnosis.[1,2,3,4,5] Neuromeningeal progression is the most common type of treatment failure.[5,6][Level of evidence C1] Treatment options according to Kadish stage include the following:[7] The mainstay of treatment is surgery and radiation therapy. However, esthesioneuroblastoma is a chemosensitive neoplasm, and the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy can facilitate resection.[5,7,8,9] Endoscopic sinus surgery offers short-term outcomes similar to open craniofacial resection.[10]; [11][Level of evidence C2] Other techniques such as stereotactic radiosurgery and proton-beam therapy (charged-particle radiation therapy) may also play a role in the management of this tumor.[3,12,13] Routine neck dissection and nodal exploration are not indicated in the absence of clinical or radiological evidence of disease.[14] Management of cervical lymph node metastases has been addressed in a review article.[14] Reports have indicated promising results with the increased use of resection and neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with advanced-stage disease.[2,5,15,16,17]; [18][Level of evidence C1] Chemotherapy regimens that have been used with efficacy include the following: References: Information about National Cancer Institute (NCI)–supported clinical trials can be found on the NCI website. For information about clinical trials sponsored by other organizations, see the ClinicalTrials.gov website. The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above. This summary was comprehensively reviewed. This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages. Purpose of This Summary This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of childhood esthesioneuroblastoma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions. Reviewers and Updates This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should: Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary. The lead reviewers for Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma Treatment are: Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries. Levels of Evidence Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations. Permission to Use This Summary PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]." The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is: PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/hp/child/esthesioneuroblastoma-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 29337483] Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images. Disclaimer Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page. Contact Us More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us. Last Revised: 2024-08-07 This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Learn how we develop our content. Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.Topic Contents

Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Incidence

Anatomy

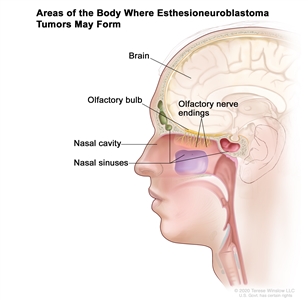

Figure 1. Esthesioneuroblastomas form in the olfactory nerve endings in the upper part of the nasal cavity. The olfactory nerves (sense of smell) pass through the many tiny holes in the bone at the base of the brain to the olfactory bulb. Esthesioneuroblastomas may spread from the nasal cavity to the nasal sinuses or to nearby tissue. They may also spread to the brain or to other parts of the body (not shown).Clinical Presentation

Histology and Molecular Features

Prognostic Factors

Stage Information for Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma

Stage Description A Tumor confined to the nasal cavity. B Tumor extending to the nasal sinuses. C Tumor extending to the nasal sinuses and beyond. D Tumor metastases present. Special Considerations for the Treatment of Children With Cancer

Treatment of Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma

Latest Updates to This Summary (08 / 07 / 2024)

About This PDQ Summary

Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]